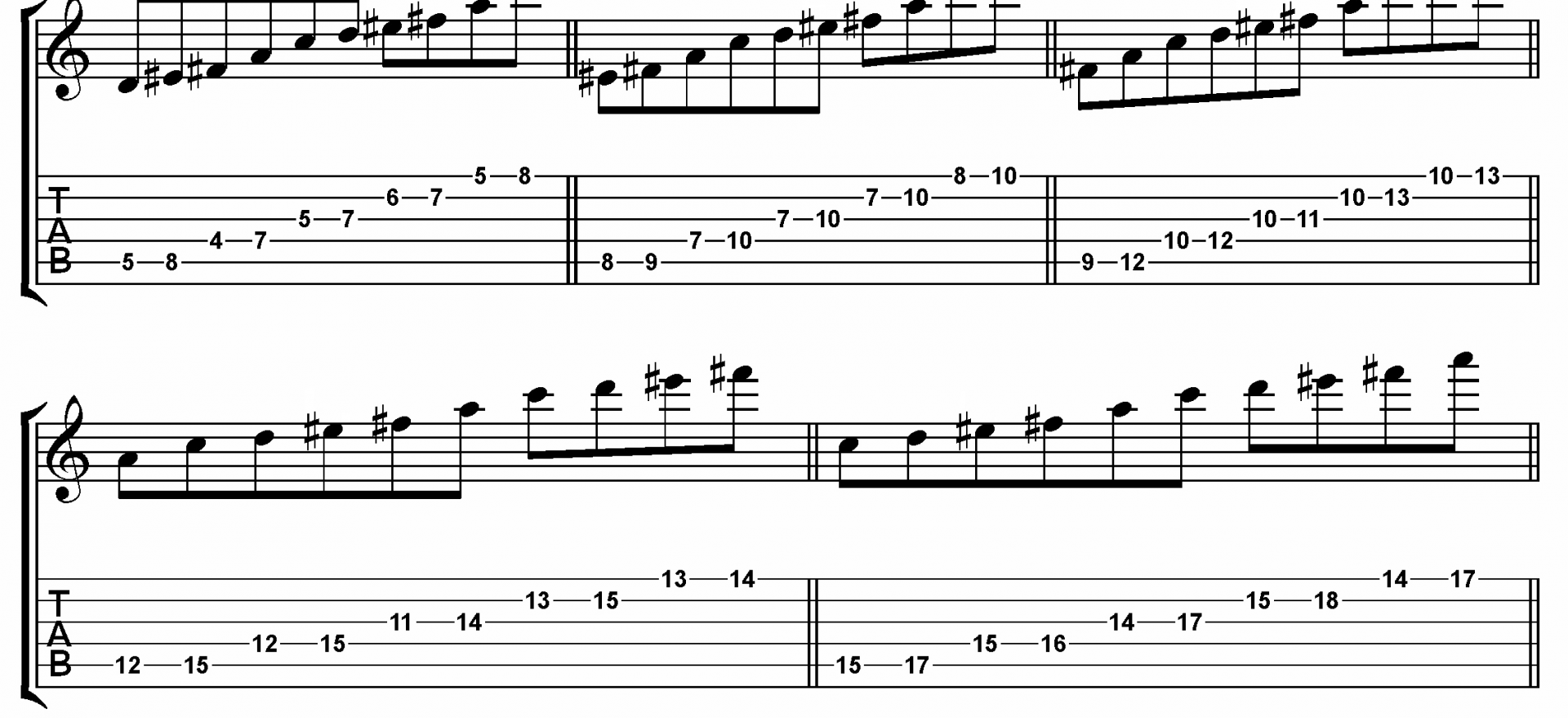

QUARTAL HARMONY

12 September 2020

“MODAL” PENTATONICS

15 September 2020Suspended Triads

… Being Suspended …

While studying a new song or a new harmonic progression, at some point you could have come across sus2 or sus4 chord symbols. Well, if you are asking yourself what these chords are, the answer is: suspended chords (in fact, “sus” is short for suspended).

As we all know, a triad is made of a root, third and fifth. Of these three notes, the 3rd is particularly important because it tells if a chord is either major or minor; nonetheless, it sometimes happens to find a chord whose structure is 1-2-5 or 1-4-5. The former is a sus2 while the latter is a sus4 (or simply sus).

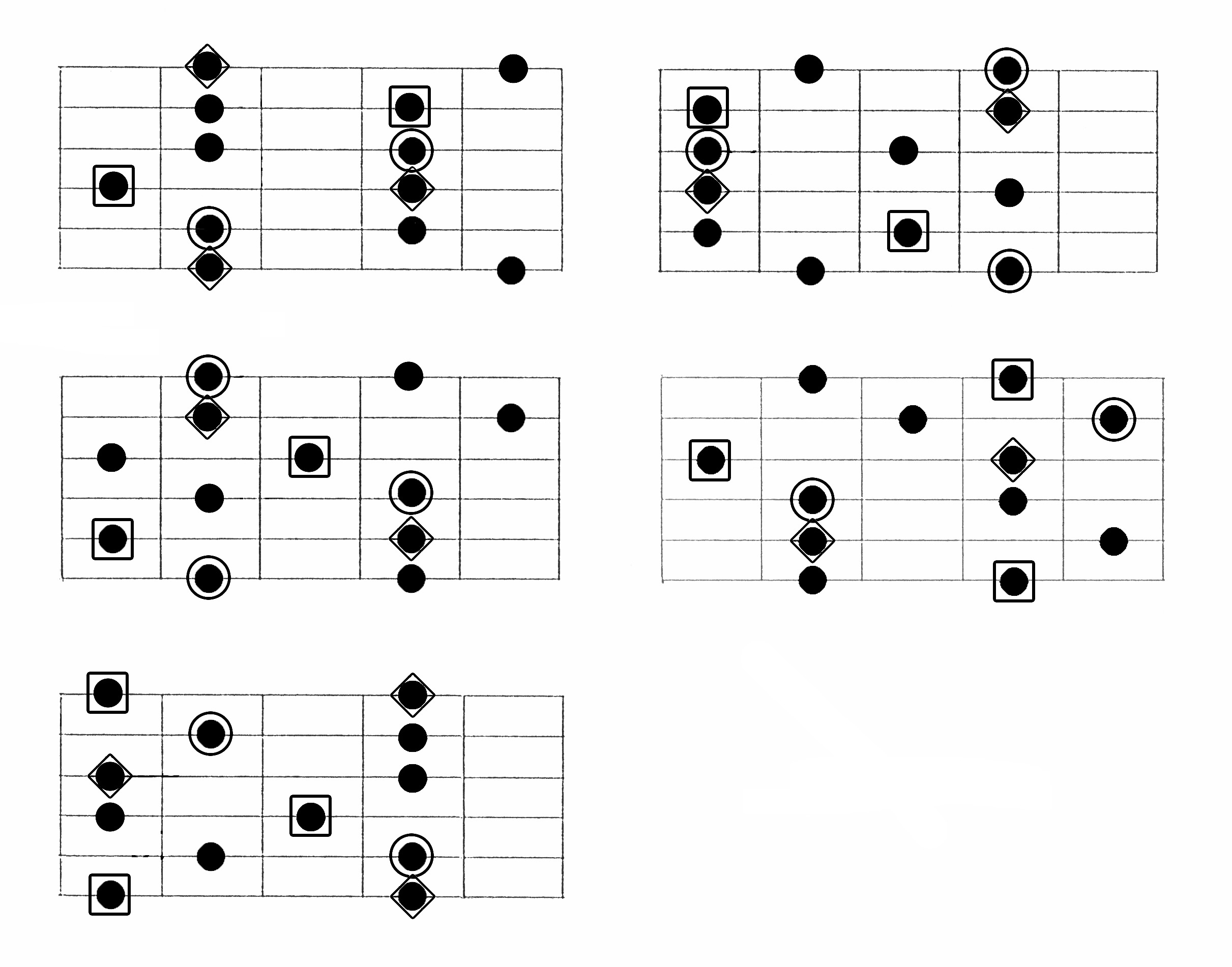

[here you can find how to play them on the guitar]

“Notes Outside the Harmony”

From an “historic” perspective, these chords are first found in tonal context as a consequence of embellishments: ritardo or appoggiatura. Basically, the 3rd of the chord was preceded by the 4th (or, less often, from the 2nd) that was then resolving on it. Once composers started to use this passing note without resolving it, the chord became “independent”, so to speak, and acquired a “suspended mood”.

If you are playing in C Major and you play a Csus chord, this will still be a tonic chord, but its sound will be “softer” than the basic C triad.

Harmonizing the Scale with Sus Chords

Is it possible to harmonize the major/minor diatonic scale with suspended triads?

Yes, it is! Just like we did with triads.

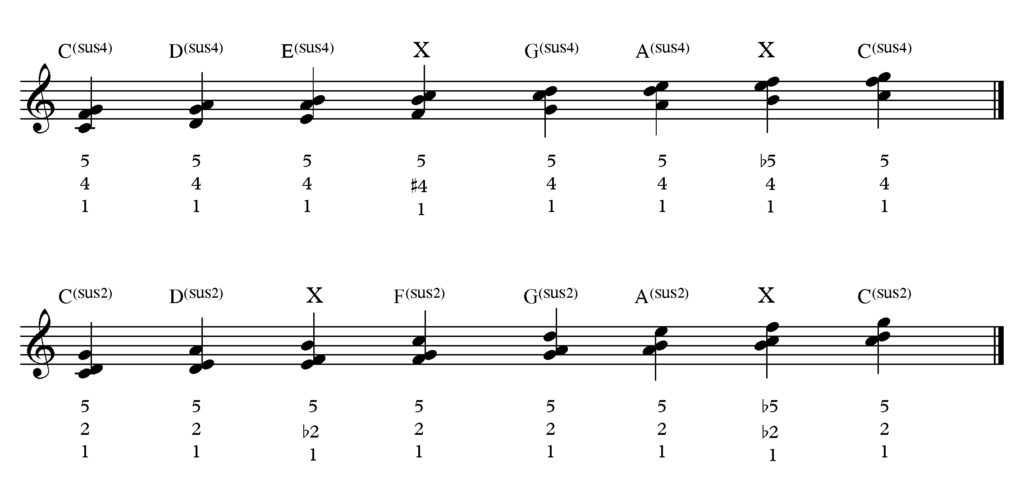

As the above image shows, it is possible to build sus2 and sus4 on five out of seven notes of the diatonic scale; in both cases we also find two “altered” suspended chords (I don’t think they have a proper name that defines them).

If we consider sus4 chords, the harmonization of the Major scale gives us these chords on the IV and VII degrees. In fact, if we think of the modes built on these two scale, they’re Lydian (with the augmented 4th) and Locrian (with the diminished 5th).

Let’s make it clear by taking the C Major scale as a reference:

| I | Csus | C – F – G | F – G – C | Fsus2 | IV |

| II | Dsus | D – G – A | G – A – D | Gsus2 | V |

| III | Esus | E – A – B | A – B – E | Asus2 | VI |

| IV | Fsus♯4 | F – B – C | B – C – F | Bsus♭2♭5 | VII |

| V | Gsus | G – C – D | C – D – G | Csus2 | I |

| VI | Asus | A – D – E | D – E- A | Dsus2 | II |

| VII | Bsus♭5 | B – E – F | E – F – B | Esus♭2 | III |

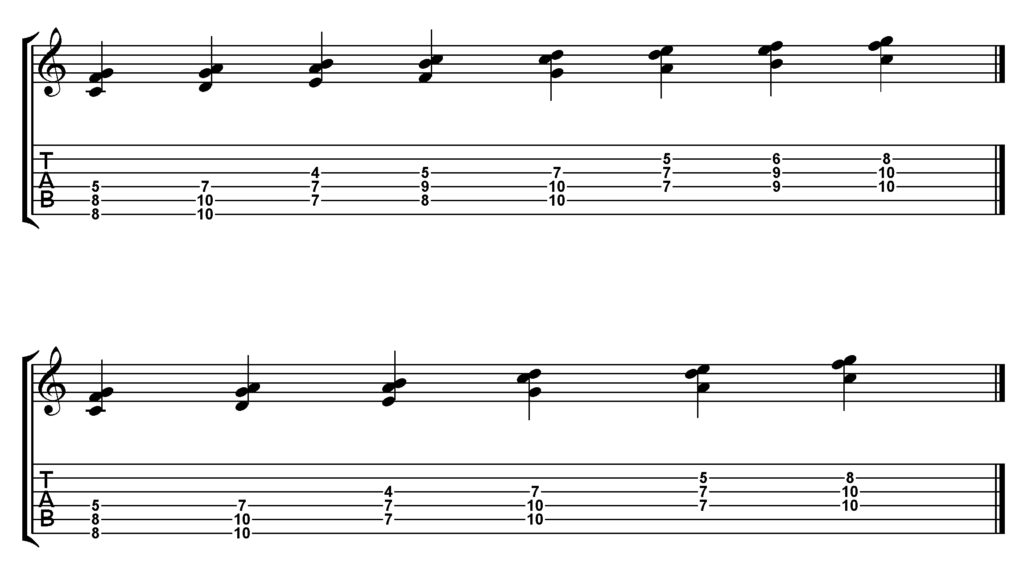

And here how to play the sus4 chords on the guitar (first they’re build on every scale degree, then the two “altered” chords are omitted):

Chords & Inversions

Once we think of the sus chord as a “real” chord (instead of a transitional moment before the major or minor triad) we can consider its inversions, just like we did with triads.

Let’s take Csus (C-F-G); its first inversion will be F-G-C, while the second inversion G-C-F.

We can see right away that F-G-C is actually Fsus2! This means that on the guitar we’ll be able to use the same fingerings for both sus2 e sus4, because one is the inversion of the other; for instance, Csus2 (C-D-G) has the same notes of Gsus4 (G-C-D). From here we can make a general statement: a sus2 chord corresponds to a sus4 an ascending 5th/descending 4th apart and so a sus4 corresponds to a sus2 an ascending 4th/descending 5th apart.

What I’ve called second inversion is made of two 4th intervals, which brings us to quartal harmony.