HOW SCALES ARE TAUGHT ON GUITAR?

20 Novembre 2018

RITMO, TEMPO, MISURA, DIVISIONE

24 Febbraio 2019After speaking about major scale and how the fingerings can be organized on the guitar, I’d like to talk a little bit about harmony.

I’ll try to keep it simple, following a straight path that starts from the fundamentals and adds a bit at a time.

Before starting, remember that in the end comprehension of music can only come through “active” listening,

otherwise it’s just words.

The Harmonic Thinking

Tonality represents a system basically built on harmonic thought (meaning: on the concept of chords). That’s what makes it different from ancient modality, which came before and was a system of melodic organization. (“modern” modality is still somewhat different and I’ll be covering all this aspects in due course).

Sure, also in XIII Century compositions you’ll find what we call chords, but at that time they were not conceived as autonomous unities but rather as the consequence of the intersection of single voice lines (the so-called counterpoint).

[Even if, as said before, my idea is to start from fundamentals, once in a while I’ll have to refer to more specific concepts, like I did now, because I’m also addressing -and maybe in particular- to those who already have some theory and instrumental knowledge, but still have a feeling that something’s not quite fitting yet. This had been my feeling for quite some time during my studies and that’s why I felt the necessity to write all this]

Harmony And Tonality

At the very basis of tonality we have the major (and minor) scale, which is deeply linked to the harmonic thinking.

During the XVI Century composers started to organize the compositional process in terms of chords (triads). Each chord came to have a specific function depending on the position of its root in the scale and eventually three chords were found as having a fundamental role in the musical development and came to be known as Tonic, Subdominant and Dominant.

(Even if in reality composers had already been doing so, the actual codification of this system came at a quite late stage, mostly thank to theoreticians as Jean Philippe Rameau in ‘700 and Hugo Riemann a century later).

Harmonic Functions In The Major Scale

Let’s start then by considering the major scale.

I won’t be discussing here the different type of triads and how there are built, hoping you all know how this works; I’ll analyze right away “how they work” inside the tonal world.

Tonic chord (T) is the one built on the Tonic of the scale. It represents the stability, home. Peace and love.

Subdominant chord (S) is built on the IV degree and represents a slight departure from the Tonic influence.

Dominant chord is the one built on the V degree and it introduces a feeling of tension that asks for the return to the Tonic (mostly because it contains the VII degree of the scale, called leading note).

In a major tonality these three chords are also major and they make no other chord necessary for that tonality to be expressed.

Notes In Common

Each note of the scale belongs to one or more of these chords:

the I degree (Tonic) is in common to the Tonic and Subdominant chords, while the V degree is shared by the Tonic and Dominant chords; the other notes belong to just one triad.

In practice:

- Tonic and Subdominant have one note in common and their roots are an ascending 4th (or descending 5th) apart;

- Tonic and Dominant have one note in common and their roots are an ascending 5th (or descending 4th) apart;

- Subdominant and Dominant have no note in common and their roots are an ascending 2nd (or descending 7th) apart.

Chords are of no use if they’re not supported by a melody. Here lies the great power of music. Even if we just think in terms of chords, it’s the way in which the single voices are developed that makes the difference, and so becomes crucial what we call the voicing of the chords.

Connecting The Chords

From Tonic In Root Position

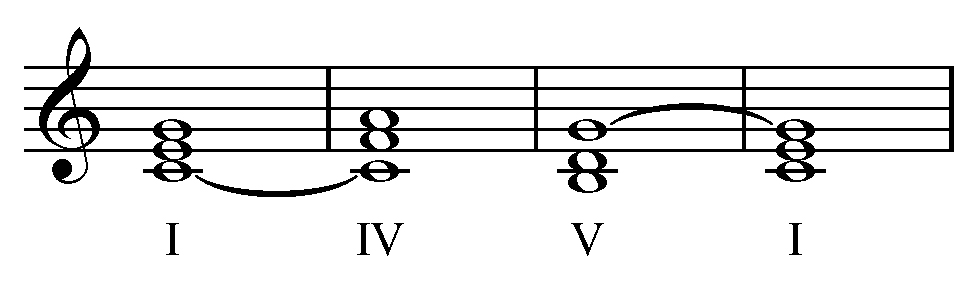

First, let’s consider the Tonic chord in root position (for those of you who don’t know, this means that its root is the lowest note), followed by the Subdominant and the Dominant and back to the Tonic:

If you listen to this sequence of chords I’m sure you can have no doubt C is the Tonic. This is what we call a cadence (which is sort of a musical “punctuation”).

The basic principle beneath the choice of this particular voicings is the idea of the “shortest way”: if two chords have a note in common, this remains in the same voice, while the others move to the closest chord-tone of the following chord; if there’s no note in common all voices move to the closest tone of the next chord.

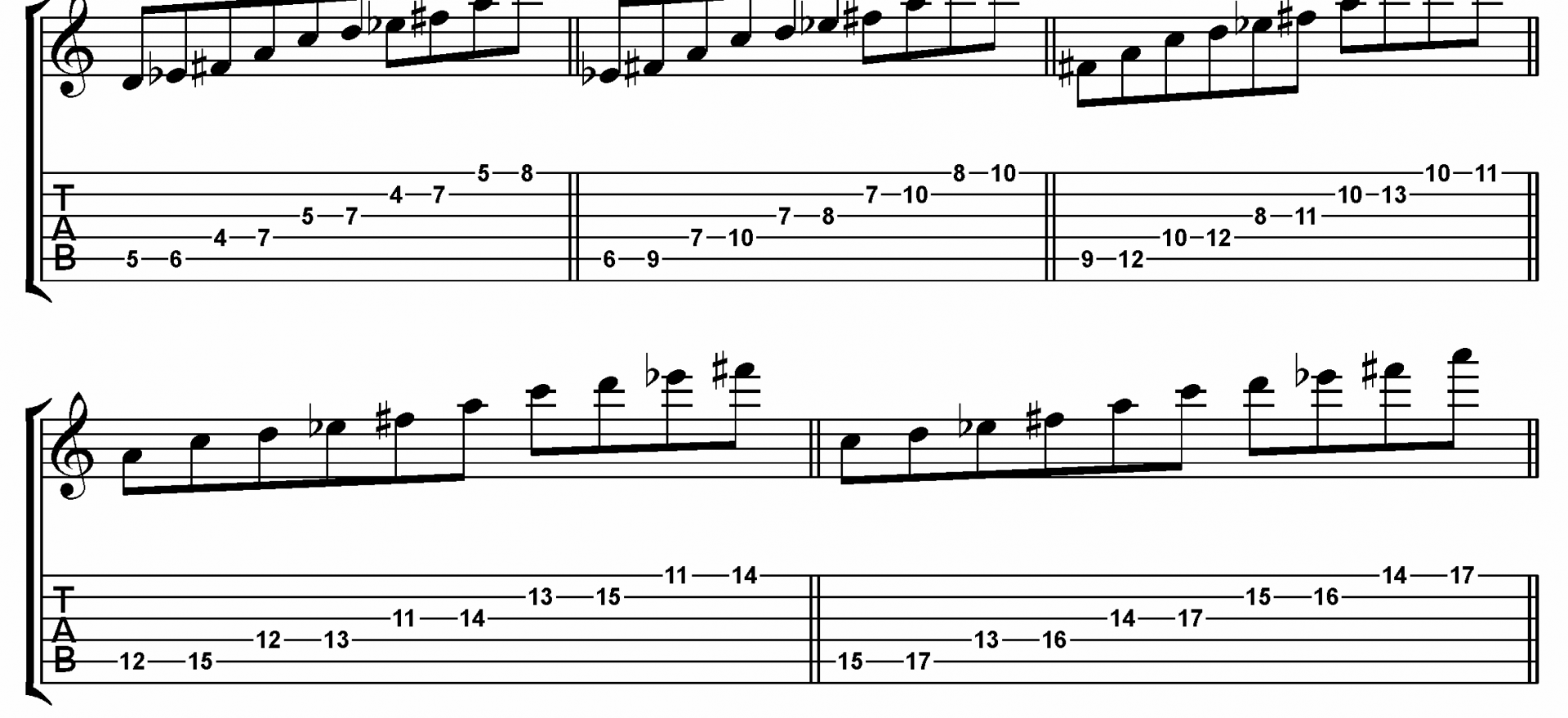

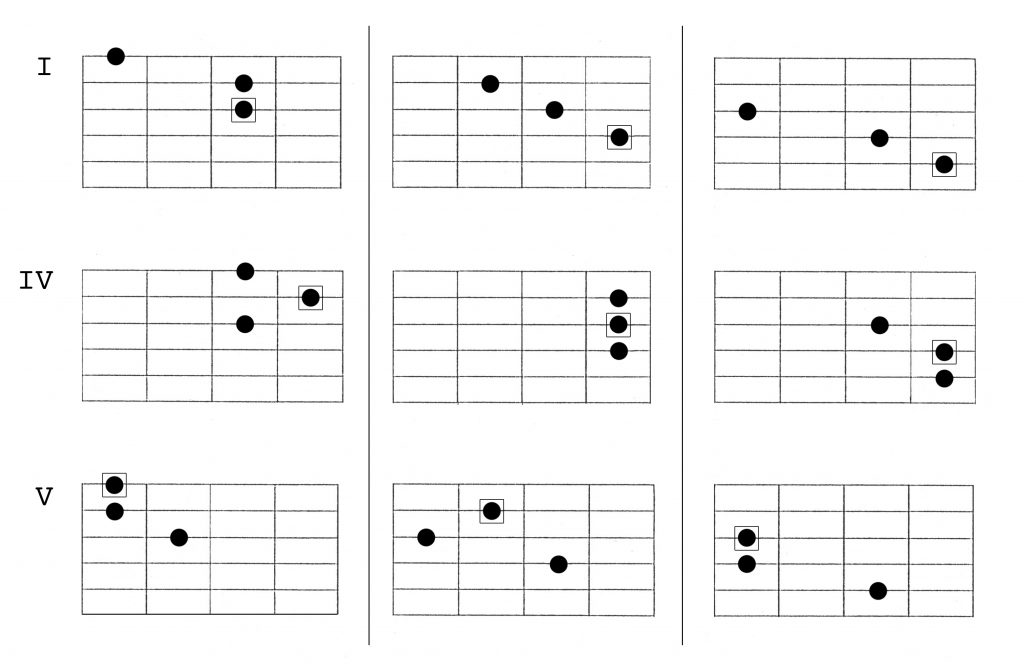

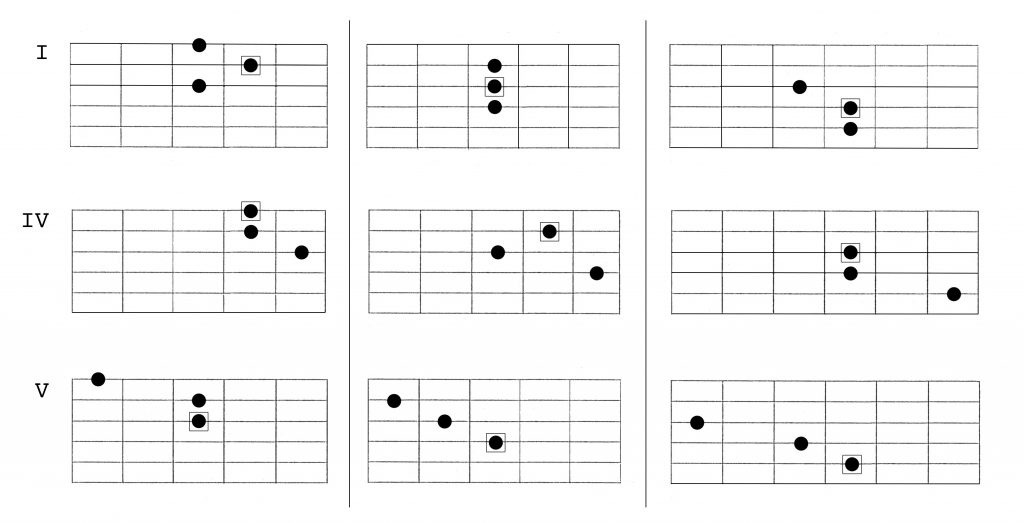

On the guitar, each of the above chords can be played using three different shapes:

In the above figure each diagram in a row shows the three shapes for each chord, by using three different sets of strings. If you read the scheme “vertically”, the fingering for the Tonic (I), Subdominant (IV) and Dominant (V) chords is shown in a “relative position”, so to move from one chord to another remaining in the same neck position.

You may have noticed there are only three string-sets shown. This is because the chord shape for the 4-5-6 strings set is the same of the 3-4-5 strings set. Simply move the latter starting from the sixth string and you’ll be fine.

Notes in the box represent the root of each triad (not the Tonic of the scale).

If you play the shapes of one of the figure you’ll end up with the same exact chord (differing just on the timbre).

From Tonic In First Inversion

Now that you get the idea, we can do the same starting from the Tonic chord in first inversion (with its third on the bass):

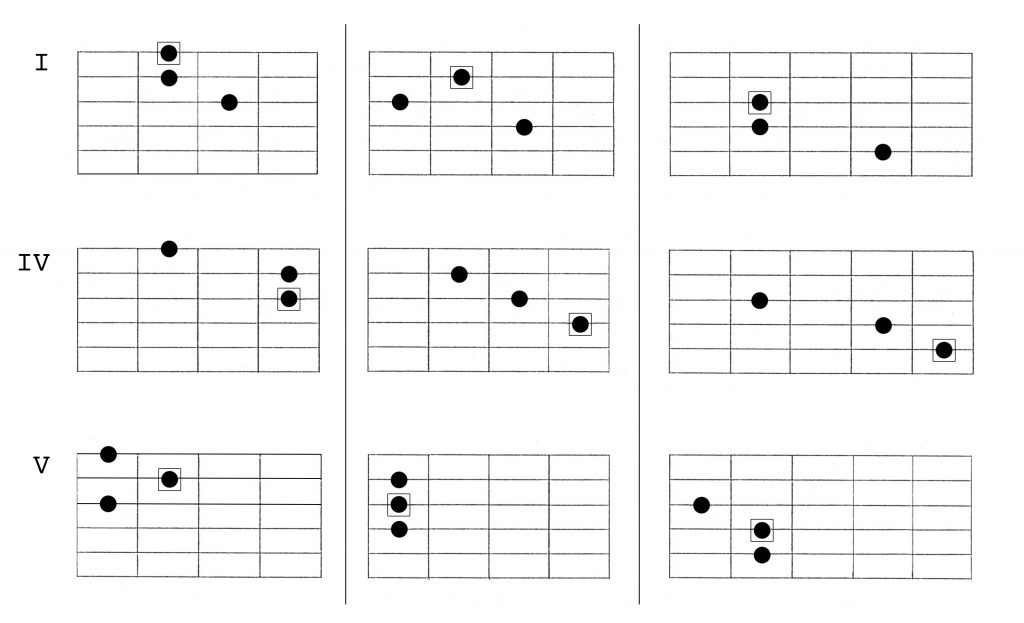

From Tonic In Second Inversion

Finally, starting from the second inversion (fifth on the bass):

It can be noted that in every figure the shapes used are always the same, they only change in their relative position.

Now it’s your turn to experiment by using different rhythms, arpeggiating the chords or changing their order and using them to harmonize a melody in a major tonality.

Let’s see what you come up with.